Gavin Ovsak is one of those guys who never seems to slow down. On top of his classwork at Harvard medical school, he’s got a side hustle—writing an original software program to help doctors make better decisions.

“It’s fun for me,” explains the 23-year-old Minnesota native, who studied biomedical engineering and computer science at Duke as an undergraduate. He admits he sometimes lets eating and cleaning slide when he’s really engaged in one of his projects.

There’s a term for people like Ovsak—the kind of go-getter who would actually choose to take on a complicated programming challenge on top of a heavy load of demanding schoolwork. Educational psychologists Adele and Allen Gottfried call people who are standouts when it comes to effort and determination “motivationally gifted.” According to the Gottfrieds, our culture has vastly underestimated just how essential motivation is to ensuring success later in life. If society learns to value this quality in the same way that it regards intelligence or leadership skills, it could be an enormous boon for children—particularly because motivation, unlike many other talents, is a quality that’s accessible to us all.

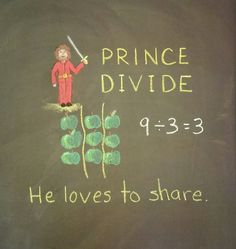

The Gottfrieds have plenty of research to back up their theories on motivation—quite literally, enough to fill a lifetime. In the late 1970s, the Gottfrieds were professors at California State University; Allen at Fullerton, and Adele at Northridge. They undertook a research project studying 130 babies born in a hospital in Fullerton, California. About 90% of the participants were Caucasian, and nearly all fell on the continuum from working- to upper-middle-class.

If there’s a secret sauce to winning at life, the motivational kids seemed to have found it. Over the next four decades, the Gottfrieds and several colleagues collected a staggering trove of data on the study participants, yielding important insights into working parents, temperament, and other topics. Researchers collected information about participants from parents, teachers and transcripts, tested their IQ and motivation levels,and even visited their homes. In all, the Fullerton Longitudinal Study has amassed an estimated 18,000 pieces of information on each of the remaining 107 participants. “It’s our life’s work,” says Allen cheerfully. “We’ll take it to our grave.”

The Gottfrieds believe one of the study’s most significant findings centers on motivation. Kids who scored higher on measures of academic intrinsic motivation at a young age—meaning that they enjoyed learning for its own sake—performed better in school, took more challenging courses, and earned more advanced degrees than their peers. They were more likely to be leaders and more self-confident about schoolwork. Teachers saw them as learning more and working harder. As young adults, they continued to seek out challenges and leadership opportunities. If there’s a secret sauce to winning at life, the motivational kids seemed to have found it.

About 19% of the babies selected at random for the Fullerton study later scored 130 or higher on an IQ Test —a widely accepted standard for intellectual giftedness. But, with a few exceptions, the Gottfrieds’ “motivationally gifted” cohort didn’t overlap with the intellectually gifted ones. In other words, these highly motivated kids excelled even when controlling for differences in intelligence or ability.

“[Motivation] in itself is accounting for a certain amount of variance in achievement that goes above and beyond IQ,” Adele explains. As the Gottfrieds watched the highly motivated kids thrive and grow, they started to look for clues about how they got that way.

The massive volume of information in the Fullerton study offered an unusual window into the home lives of the study kids. Along with colleagues, the Gottfrieds undertook the laborious task of parsing their voluminous data to tease out “pathways”—environmental influences that did or didn’t nudge kids toward intrinsic motivation when it came to learning.

The results validated some bits of conventional wisdom and deflated others. Parents who read to their kids helped them develop a love of reading, which indirectly led to higher reading achievement. But the number of books in the house had no effect on that achievement. Eight-year-old kids who were encouraged to be curious tended to like science and take more challenging science courses in high school.

Overall, parents who encouraged inquisitiveness, independence, and effort, and who valued learning for its own sake, had kids with higher levels of intrinsic motivation and achievement. Further, the effects of these practices lingered as the kids grew older. “So what you are doing at age nine not only has an immediate impact but also a follow-up impact over time,” Adele notes.

The findings echo those of other experts. In study after study, external rewards like money or status tend to lower people’s enjoyment of an activity, even if they previously liked doing it. So in order to set kids up for genuine success in life, they need to be intrinsically motivated—that is, to see learning and taking on new challenges as its own reward. “Teaching the desire to learn,” the Gottfrieds wrote in 2008, “may be as important as teaching academic skills.”

“Why are we hung up on IQ tests?”

The idea that success depends on qualities other than intelligence has gone mainstream in recent years. Psychologist Angela Duckworth popularized the concept of grit—sticking to a goal despite obstacles—along with research about its predictive qualities for success. Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck has spent years documenting the impact of a “growth mindset,” wherein people value hard work and dedication over innate ability. Still, these concepts are in many ways pushing against history. “The whole century of research, when you see giftedness, it’s intelligence. And we said, you know, giftedness can come in many forms,” Allen says with impatience. “Why are we hung up on IQ tests?”

The blame rests, at least partially, on Stanford psychologist Lewis Terman, who developed the test used for measuring intelligence known as the Stanford-Binet. In 1922, he and his researchers plucked children out of California schools based on teacher recommendations. Those who scored above a certain threshold on an IQ test were deemed gifted and enrolled in Terman’s pioneering longitudinal study.

Scholars have been arguing for decades about what lessons we should draw from the lives of the “Termites.” But one of its clear legacies is the quantification of ability. For the past century, an IQ above 130 has generally been accepted as a standard marker for intellectual giftedness.

“Giftedness can come in many forms. Why are we hung up on IQ tests?” Over the past two decades, most educators and institutions have adopted the expansion of that definition—but few seem willing to jettison its core. In a 2011 study, two Florida State University professors found all 50 states have “moved beyond” IQ tests as a solestandard for identifying gifted or high-ability kids. According to the authors, many states now look at multiple criteria when assessing giftedness, either through averaging several categories (ability, leadership, and creativity, for example) or selecting kids who stand out on one or more of them.

However, a majority of states still require intelligence and achievement testing. And the authors found only three states listing motivation as a category in its definition of giftedness. Grit may be the darling of the TED Talk crowd, but the system still places major emphasis on test scores.

René Islas of the National Association of Gifted Children says it is difficult, if not impossible, to know how many school districts may be using motivation as part of giftedness identification, since so many states also allow local districts to formulate their own criteria.

Islas is quick to point out that identification is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to gifted education. He tells parents to focus less on the label than on the services they think their children need. But he does agree that the system can overlook deserving kids. A 2015 studyanalyzing data from one state found that kids who were poor, black, Latino, or English-language learners were two and a half times less likely to be identified as gifted even when they scored equally well as peers on third-grade math and reading tests. Kids who get the official nod as “gifted” often have access to greater opportunities—so Islas thinks it’s crucial that educators keep working to get it right.

“You can enjoy what you do in life”

But the Gottfrieds’ research on motivation is important for reasons that go beyond gifted education. The Gottfrieds believe schools and parents can help all kids find their passion for learning. “Education is so skills oriented, so competency oriented, they just seem to forget about motivation,” Allen complains. Adele says one of the most important thing parents can do for their kids is stimulate their curiosity and give them the chance to become good at something they enjoy – whether they fall into a gifted category or not. “Everybody could potentially be motivationally gifted,” she says, given the right encouragement.

Yet that message may have a hard time resonating in the current educational climate, with its relentless push to rack up achievements earlier and faster.

“What message are we giving kids? You don’t have to suffer through your job to get to the weekend. You can enjoy what you do in life.“ “Focusing on intrinsic motivation doesn’t happen because it’s a complete contrast to what society is telling kids,” says educator Sheri Werner, the principal of a public charter middle school in west Los Angeles. Werner believes educators need to connect with kids by teaching them in a way that feels relevant to their lives. But her priorities sometimes put her on a collision course with parents, particularly as kids move into higher grades.

“There’s a lot of fear that if we let kids learn what they want to learn, they won’t get into college,” Werner says. She’s seen parental anxiety escalate over the years as competition mounts in universities and the job market. But she believes schools do children no favors when they dissuade them from exploring the subjects that naturally interest them, force-feeding them AP calculus instead. “What message are we giving kids? You don’t have to suffer through your job to get to the weekend. You can enjoy what you do in life.“

The Gottfrieds are living embodiments of this ethos. They are still vibrantly engaged in their research, eager to debate the parameters of their latest findings. As the Fullerton study babies approach middle age, the metrics have moved from tabulating degrees and grade point averages to other, more subjective definitions of achievement, like life satisfaction and relationships. Recently, Allen helped design a survey to measure personal success.

“The most informative item in the scale is very simply accomplishing the goals you set out,” he says. “It goes beyond education, it goes beyond money, it’s your own personal success.” They’ve also spent time looking at leadership, which, not surprisingly, dovetails with their intrinsic motivation research. Fullerton study kids who showed higher levels of intrinsic motivation at the age of nine have turned out to be more motivated to lead in their 20s—maybe because they genuinely enjoy the challenge.

But a rare note of regret creeps in when the Gottfrieds talk getting their work out to a popular audience. They are academics, not journalists. “We don’t know how to write for the public,” Allen admits, recalling times they left non-experts baffled by detailed descriptions of latent variable analysis and structural equations—tools of the trade for research psychologists. “They told us we lost the audience,” Adele agreed. They have talked with colleagues at academic conferences about ways to reach more practitioners and parents. But perhaps the rest of us need to meet them halfway. After all, they’ve devoted their entire adult lives to the research. Now, it’s up to everyone else to listen.

You can access the original article here.