The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the “First 1000 Days”

Every child has a right to optimal cognitive, social, and emotional behavioral development. The cognitive, social, and emotional parts of the brain continue to develop across the lifespan. However, the brain’s growth and development trajectory is heterogeneous across time. A great deal of the brain’s ultimate structure and capacity is shaped early in life before the age of 3 years. The identification and definition of this particularly sensitive time period has sharpened the approach that public policies are taking related to promoting healthy brain development. The ramifications are large because failure to optimize brain development early in life appears to have long-term consequences with respect to education, job potential, and adult mental health. These long-term consequences are the “ultimate cost to society” of early life adversity.

Among the factors that influence early brain development, three stand out has having particularly profound effects: reduction of toxic stress and inflammation, presence of strong social support and secure attachment, and provision of optimal nutrition. This article focuses on the latter by first describing the important features of brain development in late fetal and early postnatal life, discussing basic principles by which nutrients regulate brain development during that time period, and presenting the human and pre-clinical evidence that underscores the importance of sufficiency of several key nutrients early in life in ensuring optimal brain development.

Policy makers have recently placed a great deal of emphasis on the “first 1000 days” and “0–3” (years) as golden opportunities to influence child outcome. The first 1000 days correspond roughly to the time from conception through 2 years of age. However, a closer examination of the trajectory of anatomical and functional brain development combined with clinical and epidemiological studies of neurodevelopmental outcome suggests a slightly broader window extending to three years. Nevertheless, the same basic principles of brain development discussed below continue to apply.

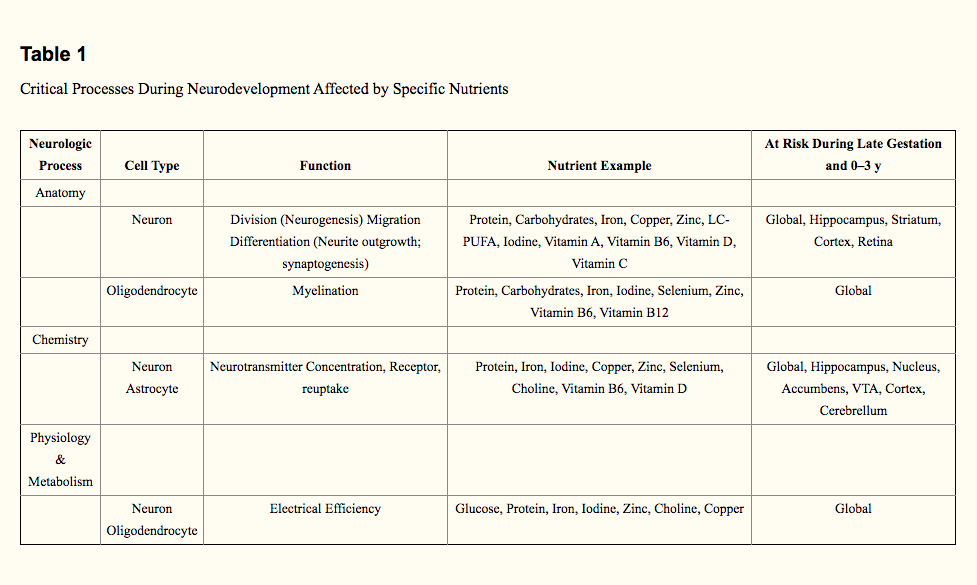

The brain is not a homogeneous organ. Rather, it is comprised of multiple anatomical regions and processes (eg, myelination), each with unique developmental trajectories. Many of these regions have developmental trajectories that begin and accelerate in fetal life or shortly after birth. For example, myelination abruptly increases at 32 weeks gestation and is most active in the first 2 postnatal years. The monoamine neurotransmitter systems involved in mediating reward, affect, and mood begin their development pre-natally, continuing at a brisk pace until at least age 3 years. The hippocampus, which is crucial for mediating recognition and spatial memory begins its rapid growth phase at approximately 32 weeks gestation, continuing for at least the first 18 postnatal months. Even the prefrontal cortex, which orchestrates more complex processing behaviors, such as attention and multi-tasking, has the onset of its growth spurt in the first 6 postnatal months. Keeping brain areas on developmental trajectory is critical not only for promoting behaviors served by the individual regions, but also more importantly, to ensure time-coordinated development of brain areas that are designed to work together as circuits that mediate complex behaviors.

Early life events, including nutritional deficiencies and toxic stress, can have differential effects on developing brain regions and processes based on the timing, dose, and duration of those events. The importance of timing in particular should be underscored. As noted, the timing of peak rates of development of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex differ. The timing of an adverse environmental event that, for example, affects neuronal dendritic arborization will determine whether the hippocampus or the prefrontal cortex sustains greater damage and compromise of functional integrity. The earlier the insult, the more likely the hippocampus will be affected more than the prefrontal cortex. In a brain circuit that requires balanced hippocampal and prefrontal input (eg, the ventral tegmental area loop), such imbalance can result in significant behavioral pathology, such as schizophrenia.

Neuroscientists and psychologists use terms such as “critical period” and “sensitive period” to describe time epochs of opportunity and vulnerability. Critical periods are typically conceptualized as early-life epochs when alterations to brain structure or function by an environmental factor (eg, nutrition) result in irreversible long-term consequences. Sensitive periods imply an epoch when the brain (or brain region) is more vulnerable to environmental factors, including nutrient deficiencies, but when the effect is not necessarily deterministic. The term “sensitive period” can also be used in a positive manner to describe times when the brain may be particularly receptive to positive nutritional or social stimulation. Both concepts rely on the observation that the young, rapidly developing brain is more vulnerable than the older brain, but also retains a greater degree of plasticity (eg, recoverability). Over time, the distinction between critical and sensitive periods has become blurred as more research emerges. Although the distinction may become less meaningful, either concept emphasizes the need for pediatricians to focus on making sure the child is receiving adequate nutrition to promote normal brain development in a timely fashion.

The vulnerability of a developing brain process, region, or circuit to an early life nutrient deficit is based on two factors: the timing of the nutrient deficit and the region’s requirement for that nutrient at that time. For example, the risk of iron deficiency varies with pediatric age. Peak incidences are seen in the fetal/newborn period, 6–24 months of age, and during the teenage years in menstruating females. Each of these epochs has different iron-dependent metabolic processes occurring in the brain. Thus, the behavioral phenotype of iron deficiency varies by the child’s age. This type of timing and dose/duration information can be leveraged to change clinical prescription of certain nutrients. For example, consensus panels determining maternal requirements for folic acid in pregnancy based their recommendations on knowledge of the biology of folic acid in the developing fetal brain and long-term infant outcome.

All nutrients are important for brain growth and function, but certain ones have particularly significant effects during early development. The effect of a nutrient deficit on the developing brain will be largely driven by the metabolic physiology of the nutrient, ie, what processes it supports in brain development and also by whether the deficit coincides with a critical or sensitive period for that process. Key nutrients for brain development are defined as those for which deficiency that is concurrent with sensitive or critical periods early in life results in long-term dysfunction.

Biological proof of single nutrient effects on brain development are difficult to demonstrate in young children because of the subtlety and variability (based on timing) of nutrient effects, the limited behavioral repertoire of the youngest, most vulnerable children, the lack of brain tissue evidence of nutrient sufficiency or deficiency, the co-occurrence of multiple nutrient deficits in many at-risk populations, and non-nutritional confounding variables such as poverty and stress. Observational studies dominate the literature, but even randomized control trials (RCTs) are at risk for misattribution of effects or misinterpretation of lack of effects because of violations of various nutrient-brain interaction principles outlined above.

Another scientific approach to the problem is cross-disciplinary, translational research that depends on combining pre-clinical and human studies. This approach makes the assumption that basic biological principles of nutrient-brain interactions are conserved across species. This approach has the advantage of controlling for potential confounding variables in order to isolate the effect of the nutritional variable of interest. The risk, however, is in failing to accurately relate the preclinical model’s nutritional metabolism and brain development to the human.

In the following section, we highlight key macro- and micro-nutrients that are critical in brain development in the first 1,000 days of life by presenting both human and pre-clinical data that underscore their significant impact. These deficiencies, and thus likely also their harmful effect on neurobehavioral development, are most prevalent in low- and middle-income countries, although they persist in high-risk, e.g., low-income, refugee, food-insecure, populations in high-income-countries as well.

Protein

Growth failure is one of the most common manifestations of malnutrition worldwide. In its fetal form, it is referred to as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), typically defined as fetal weight less than the 10th percentile for gestational age. It is likely that multiple nutrients, both macro- and micro-, are compromised in IUGR. Poorer developmental outcome following IUGR may thus be due to protein or energy undernutrition, deficiencies of key micronutrients or both.

Consensus panels agree that IUGR and postnatal growth failure in the first three years profoundly affect neurodevelopment. One recent systematic review of 38 studies found that children with IUGR born at 35 weeks of gestation or later scored 0.5 standard deviation units lower across all neurodevelopmental assessments. This difference was 0.7 standard deviation units in children with IUGR born before 35 weeks gestation. Two individual landmark studies in the 1970’s and 1980’s in four Guatemalan villages by Pollitt et al demonstrated the importance of macronutrients, specifically protein, during the prenatal period and early childhood in achievement of full developmental trajectory. Early postnatal growth is also a key determinant. Linear growth rate before, but not after 12 months of age, and infant weight before four months of age significantly predicts child intelligence quotient (IQ) at age 9 years. Neither child linear growth nor weight after 12 months is associated with child IQ nine years later.

Pre-clinical models of early life malnutrition indicate that protein or protein-energy restriction results in smaller brains with reduced RNA and DNA contents, fewer neurons, simpler dendritic and synaptic head architecture, and reduced concentrations of neurotransmitters and growth factors. IUGR modifies the epigenetic landscape of the brain, providing a potential mechanism for long-term neurodevelopmental effects.

LC-PUFAs

The impact of supplementation with long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA)— particularly docosohexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6n-3) and arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6)– during gestation, lactation, and early childhood on childhood cognition has been extensively reviewed. Gestational and early postnatal LC-PUFA supplementation has been associated with improved cognition and attention in some studies, but meta-analyses report mixed findings. Nevertheless, a recent study found that the benefit of LC-PUFA given in the first year may not be apparent until after 3 to 6 years of age, emphasizing the importance of extending the observation period of nutritional studies to accommodate longitudinal follow-up beyond early childhood.

Preclinical models show that DHA is necessary for neurogenesis and neuronal migration, membrane fatty acid composition and fluidity, and synaptogenesis. The LC-PUFAs have a profound effect on monoaminergic, cholinergic, and GABA-ergic neurotransmitter systems. In particular, the visual system and areas of the prefrontal cortex that mediate attention, inhibition, and impulsivity are targets of early PUFA status in non-human primate models. LC-PUFAs modify the epigenetic landscape of the brain, conferring potential long-term effects.

Eradication of the three most prevalent micronutrient deficiencies—iron, zinc, and iodine–could increase the world IQ by 10 points.

Iron

More than 50 studies in humans including observational studies, supplementation trials, and iron therapy studies, demonstrate a key role of iron in brain development. Collectively, there is general consensus that supports the principle that prevention is preferable to treatment of iron deficiency, and that the earlier the brain is protected from suboptimal iron status, e.g., the prenatal period and early infancy, the better.In a set of studies in Nepal, children whose mothers received iron/folic acid supplementation during pregnancy scored better on multiple tests of intellectual, executive, and motor function compared with placebo controls. However, subsequent supplementation of the children with iron between 12–35 months conferred no added benefit to children whose mothers received iron supplementation, nor did supplementation between 12–35 months have an effect on the intellectual, executive, or motor outcomes of children of placebo controls. Moreover, mis-timed or excessive iron may lead to worse neurodevelopmental outcomes, as recently shown in a single 10-year follow-up study of an infant iron supplementation study in Chile. In that study, 6-month-old infants with high hemoglobin who received iron-fortified formula performed significantly worse 10 years later on a battery of neurodevelopmental tasks, and infants with low hemoglobin who received iron-fortified formula performed significantly better. These results emphasize that a nutrient that is beneficial at one dose or time may be toxic at another.

Preclinical models demonstrate that the effects of iron on the developing brain relate to its role in hemoproteins and non-heme enzymes that rely on the iron molecule for their activity. Iron is necessary for normal anatomic development of the fetal brain, myelination, and the development and function of the dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine systems. Iron also modifies the epigenetic landscape of the brain.

Zinc

Meta-analyses and reviews of zinc supplementation fail to find a significant effect on child cognition or motor development, likely due to a great degree of heterogeneity in the effect sizes and study designs. Individual studies, however, reveal key beneficial outcomes when zinc deficiency is prevented in early infancy and also positive impact of zinc when given in combination with iron.

Preclinical models indicate that zinc is necessary for normal neurogenesis and migration, myelination, synaptogenesis, regulation of neurotransmitter release in GABA-ergic neuron and ERK1/2 signaling particularly in the fetal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and the autonomic nervous system. Behaviorally, early life zinc deficiency results in poorer learning, attention, memory and mood.

Iodine

Iodine’s sole role in brain development is to support thyroid hormone synthesis. The developing fetal brain is most susceptible to iodine deficiency during the first trimester, when fetal T3 production depends entirely upon supply of maternal T4. Severe iodine deficiency can result in cretinism, marked by deficits in hearing, speech, and gait and IQ of approximately 30. Iodine supplementation in early pregnancy of women at risk for iodine deficiency results in better cognitive outcomes in offspring.

Preclinical studies demonstrate that prenatal iodine deficiency results in deficits in neurogenesis, neuronal migration, glutamatergic signaling, and brain weight, and postnatal models affect dendritogenesis, synaptogenesis, and myelination. Behavioral abnormalities range from global abnormalities in severe deficiency to poorer learning and memory, sensory gating, and increased anxiety in milder deficiency.

Clinical Implications

In the pre-conceptional period, efforts should focus on nutritional counseling for women of childbearing age, screening for common nutrient deficiencies, and maintaining a healthy maternal body weight. Screening for and treating maternal iron deficiency is particularly high yield because more than 15% of U.S. women of childbearing age are iron-deficient. Weight management and reduction of obesity has become a target because of recent evidence that obesity during pregnancy is a risk to fetal brain development.

During gestation, non-nutritional factors, including maternal high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and stress, can affect fetal brain nutritional status. Seventy-five percent of the cases of IUGR in the United States are due to maternal hypertension. Fifty percent of infants with IUGR have low iron stores at birth; all have protein malnutrition. Ten percent of pregnancies are complicated by pre-gestational or gestational diabetes mellitus; up to 65% of infants of diabetic mothers are born with iron stores below the 5th percentile. Maternal stress has a direct effect on the fetal brain, but also alters how certain nutrients are trafficked in the maternal-fetal dyad.

In the postnatal period, the most obvious nutritional strategy to sustain healthy brain development is breastfeeding. Although the concentrations of many nutrients in human milk are not a function of maternal diet, others including LC-PUFAs are. Thus, nutritional support of the newborn includes nutritional counseling of the mother. Maintenance of iron and zinc sufficiency is particularly important. Even though screening for iron status in the newborn period is not routine, awareness of children at risk for low iron status at birth is important. Maternal milk is a poor source of divalent metals (eg, zinc, iron) and will not meet the needs of the child after 6 months of age.

As in pregnancy, reduction of non-nutritional factors that affect nutrient absorption and distribution to the brain is key in the postnatal period. These include infection and inflammation, which significantly affect how protein, zinc and iron are processed. In the case of iron, infection increases levels of hepcidin, which reduces iron absorption, sequesters iron in the reticulo-endothelial system, and results in functional iron deficiency.

Children from 1 to 3 years of age are particularly vulnerable because they typically ingest a diet similar to that of their adult parents. Thus, they are susceptible to poor parental food habits and can have food insecurity that causes a sacrifice of quality food for food quantity. Food sources for nutrients that are important for normal early development can be found in the American Academy of Pedaitrics’ (AAP) Handbook on Nutrition and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics website. In low- and middle-income countries children between 1 and 3 years of age are at high risk of nutritional deficiency because the local cereal-grain-based-diet is insufficient to meet the substantial nutrient requirements needed to sustain their rapid growth. Monitoring growth is routine, but growth failure is a late finding, particularly for micronutrient deficiencies. Anemia is also a late finding for iron deficiency. The AAP Handbook on Nutrition states that children of that age consuming a well-balanced diet do not need nutritional supplementation, but particular attention may need to be paid to vitamin and micronutrient status if the parental diet is assessed as risky. Finally, food insecurity, or inadequate food due to lack of money or other resources, is not only a low-income country problem, but also a common condition in the United States, where an estimated 16 million children live in food-insecure households. A 2015 AAP guideline emphasized the importance of screening for food insecurity, issuing a 2-question strategy that identifies a food-insecure child with 97% sensitivity. Identification of food-insecure households is critical so that appropriate referrals to community resources such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) can be made, thus helping to ensure optimal nutrition and brain development from pregnancy though early childhood.

Summary

Nutrition plays an important role in brain development from conception to 3 years of age. Public health policies should emphasize access to quality food for pre-conceptional, pregnant, and lactating women. Guidelines should support breastfeeding for infants during the first year and more oversight of the quality of food that children are offered from 1 to 3 years, when they are most vulnerable to the vagaries of parental diets. Obtaining dietary histories, screening for food insecurity and active teaching of parents are crucial steps the practitioner can implement at the personal level.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (R-01HD29421-19 [to M.G] and 5R03HD74262-2 [to S.C.]).

Abbreviations

| IUGR | Intrauterine Growth Restriction |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| LC-PUFA | Long-chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| DHA | Docosohexaenoic Acid |

| AA | Arachidonic Acid |